Note: to start with, we’ll use the terms teaching and learning policy and pedagogical framework interchangeably. Stick around to see how they diverge.

What makes great teaching?

Take a few minutes to indulge in some thinking about teaching. Grab a set of post it notes and write down all the things that you can think of that make great teaching, each item on a separate post it note.

Done? Now let’s build on it. You’ve just retrieved from memory what makes great teaching but let’s add in some of what the evidence suggests. We might use Rosenshine’s Principles of Instruction, or the Sutton Trust’s report into what makes great teaching, or Evidence Based Education’s Great Teaching Toolkit. This time though, let’s use the State of Victoria’s High Impact Teaching Strategies:

Having looked at this and read the linked document, you might now want to add to your post it notes about what makes great teaching.

I know what you’re thinking. There is more to great teaching that than the instructional element. So let’s build in some more. We might use Pep’s McCrea’s work on motivated teaching, or the Australian Education Research Organisation’s belonging practice guides, or the State of Victoria’s High Impact Wellbeing Strategies. Add anything else to your post it notes that you find interesting and important.

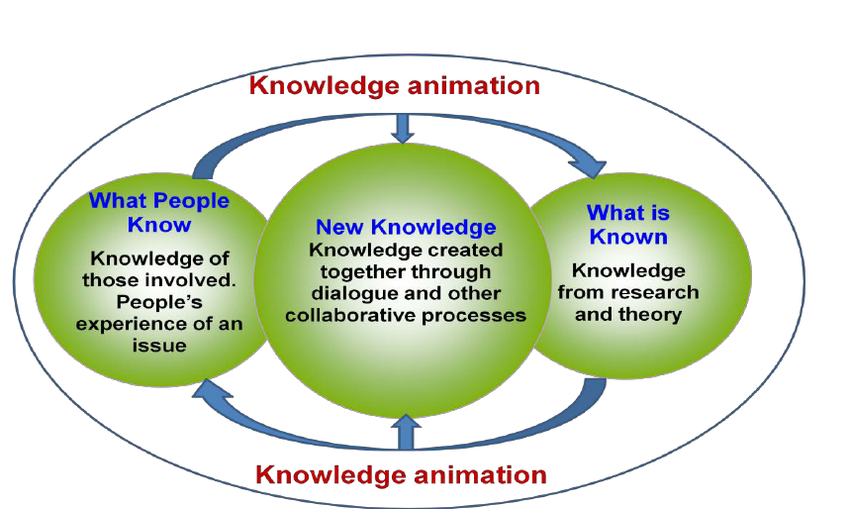

Right now you should have a whole pile of post it notes that combine what you already thought about what makes great teaching with what you might have learned from external evidence sources. By combining them together in the way that you have, you have engaged in what Louise Stoll calls knowledge animation:

However, in this thought experiment, you’ve been doing this alone. Stoll emphasises the importance of this being a dialogic, collaborative process.

Check point

The process of designing a teaching and learning policy should involve knowledge animation, not simply implementing someone else’s framework.

The process of knowledge animation, should be collaborative, not simply devised and imposed by one leader or a small group of leaders on the rest of the school.

Let’s consider why…

Bodies of knowledge

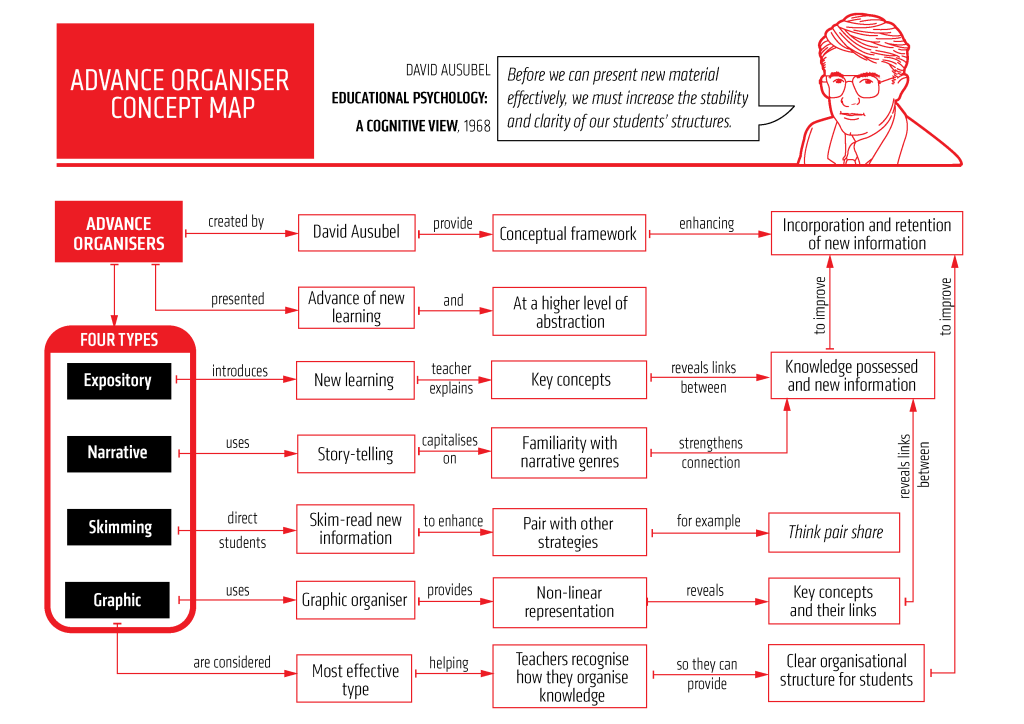

If you haven’t yet read Sarah Cottingham‘s Ausubel’s meaningful learning in action, grab a copy now. It is comfortably the most useful and relevant edubook that I have read for years and is applicable to not just teaching but professional learning and leadership too. Here’s a great summary from Jamie Clark:

The goal of teaching (and, I’d argue, professional learning for teachers) is to help others to develop bodies of knowledge. Bodies of knowledge are vast, stable, connected, organised and accessible, as opposed to disconnected island about a given topic (in this case, what makes great teaching). The key part here is organisation.

So let’s return to our post it notes. You have in front of you disconnected islands about the topic of great teaching. The next step is to organise them. Have a go now at some more knowledge animation by organising your ideas in a way that makes most sense to you.

Done? Remember, even better if you do this work in school collaboratively. How have others organised their ideas about what makes great teaching? Evidence Based Education’s Great Teaching Toolkit, for example, categorises it like this:

Why organise it? Well let’s imagine this:

Imagine if all teachers in our schools had a body of knowledge about what makes great teaching that is vast, accessible, stable, connected and organised? They’d be able to remember more, remember longer and keep learning, all of which are upstream of actually teaching and of course upstream of children’s achievement.

Here is Efrat Furst‘s model of why this is so important in learning something new. When you watch it, do so with the lens of teachers learning something new.

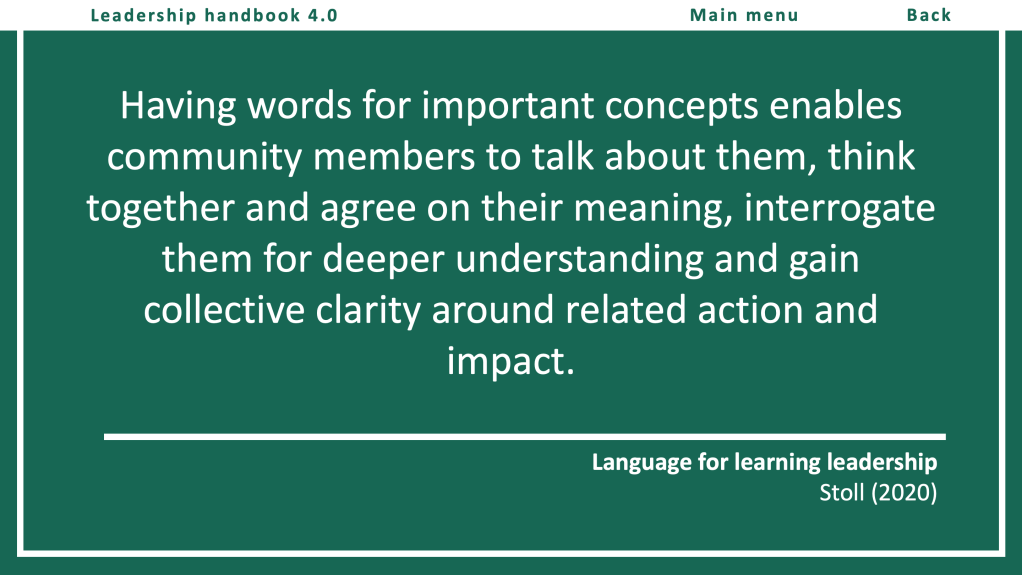

Imagine if all our teachers shared this body of knowledge too. The opportunities for discussion and refinement are endless. The process aligns us with a shared language about teaching, crucial to enabling great conversations between colleagues that moves our shared meaning forward:

Check point

A pedagogical framework provides a shared cognitive structure within which new learning can be assimilated and we can seek to achieve shared meaning.

This is arguably the most important (and probably limiting) factor to school improvement because what teachers know and do (their expertise) determines the outcomes that children achieve.

There are clear implications then for professional learning…

Meaningful professional learning

Fundamental to Ausubel’s theory of meaningful learning is that the most efficient way to build a body of knowledge is to learn more generalised concepts first and then assimilate more detailed ones. Ausubel made a related point with this insight:

Just as in Furst’s video earlier in this post, what teachers already know will determine how well they assimilate new learning. Therefore, when we’re going through the process of collaborative knowledge animation to pull together a shared pedagogical framework that works for our school, we need to think very carefully about the way that we seek to organise our collective thoughts about what makes great teaching. This is where anchoring concepts come in.

Let’s start with the concept of questioning. It comes up in every piece of evidence on what makes great teaching but not all questions are equal. Asking a class: ‘Do you understand?’ is a pretty terrible question. So we might want to teach teachers different questioning techniques, for example cold calling:

Cold calling sits beneath questioning as a more specific concept but what sits above it and what is this important? We can all think of lethal mutations of well intentioned ideas. If we introduced cold calling then did lots of monitoring of it, we could easily end up with teachers doing cold calling regardless of whether cold calling was even a sensible questioning strategy for a given situation. So I’d argue that we need specify the more general concepts that sit above questioning:

I’d say that a good place to start is with the more general concept of responsive teaching. Questioning is one element of responsive teaching. What concept sits above responsive teaching? Back to Ausubel:

Responsive teaching as a concept sits below the idea that what students already know determines what they can learn.

Here’s another example of the conceptual structure around another high impact teaching strategy – worked examples:

One particular thing that we might want teachers to learn is to narrate the thought process, which is one part of what a worked example is. But worked examples might sit below a broader concept that we need to hold that we ought to be breaking tasks and instructions down into small chunks, which itself is one way of reducing cognitive load. By presenting new learning in the context of an existing cognitive structure, the result of the work of knowledge animation, we can support teachers to come to an understanding within a range of acceptable meaning, thus reducing the likelihood of misunderstanding and in turn lethal mutations.

The more we can identify the most general, universally understood anchoring concepts, particularly in the mechanics of learning, the more likely it is that we’ll always be able to identify some prior knowledge that teachers hold that can be activated and therefore increase the likelihood of them understanding whatever new thing that we want them to learn. Step forward Mary Kennedy…

Kennedy makes the point that we focus too much on the actions of teaching and not enough on their purpose. This could give us a great set of universally understood anchoring concepts on which to build a pedagogical framework. She identified 5 persistent challenges of teaching, challenges that are as applicable to teaching the foundation stage as they are to year 13, as applicable to teaching maths as they are to art:

For me, this looks like a great set of generalised, anchoring concepts on which do pull together a school community’s ideas on what makes great teaching.

If we were to invest the time in applying this extended thought experiment to developing a teaching and learning policy or a pedagogical framework in our school (and I think we should) we might eventually end up with something that looks a bit like this:

This is by no means exhaustive. The persistent challenges of teaching on left could surely be parsed even further than the 2 or 3 concepts that I have identified. And each of these concepts can be specific even further that those on the right hand side. And that is ok because this is not a piece of work that will ever be finished! The more we learn about great teaching, the more our pedagogical frameworks need to evolve. What we do have though is a starting point for meaningful professional learning – an advance organiser.

Check point

Building a pedagogical framework through collaborative knowledge animation requires careful design of the conceptual structure to maximise the chances of teachers forming meaning within an acceptable range.

How might we use such a framework?

Meaningful professional learning using an advance organiser

Ausubel advocated for the use of an advance organiser in connecting new learning with what is already known and this post does a great job if explaining this, in particular:

…the foundational knowledge that the learner needs to do the more complex stuff, first need to be made explicit to the learner and the instruction used needs to accommodate this. Advance organisers are one way of helping the learner create those hooks, as long as the learner takes some time to process and understand the information presented in the organiser itself and of course, the organiser also must indicate the relations among the basic concepts and terms that will be used.

David Goodwin has done a great job in representing the idea and use of advance organisers:

In short, a well conceived pedagogical framework can act as an advance organiser and, if used well, can supercharge professional learning. That’s for another post…

Teaching and learning policy vs pedagogical framework

And this brings us to a important distinction to make with how we frame this work. When leaders want to scale up work in their school, we often lean towards writing a policy. There are all sorts of statutory policies that we might write and adopt with the aim of consistency of practice. Health and safety, safeguarding and pay are all organisational practices with safety, equality and fairness as their reason for existing. When it comes to teaching, paraphrasing Dylan Wiliam, there is more variation in the quality of teaching within each school than between schools and so leaders have been forever seeking ways to ensure that the quality of teaching is consistent from classroom to classroom. This is where teaching and learning policies have emerged, sometimes mandating specific practices in the pursuit of consistency. But as Greg Ashman explains, rubrics fail:

A pedagogical framework, on the other hand, is a shared understanding of how we think about teaching. Going about the knowledge animation necessary to develop this is the work of school leadership. It creates direction. It stimulates the school as a learning organisation. It provides us with a mechanism for weaving our desired values and beliefs into day to day practices through the attention to more generalised concepts. It nudges us towards appreciating the complexity of school life and rejecting the imposition of simplistic rubrics, helping us to hold competing truths in mind through disruptive experiences. The shift in thinking from policy to complexity might be an example that the nature of school leadership is changing.