We use the High Impact Teaching Strategies.

We use the Great Teaching Toolkit.

We use the Walkthrus.

We use Rosenshine’s Principles of Instruction.

These authors and many more have parsed the practice of teaching, all seeking to communicate what it is that teachers do that leads to children’s learning. They can be useful to leaders who are seeking to raise standards and it is tempting to get every teacher doing these things. Consistency!

Although there are probably some useful ideas about teaching that apply to the teaching of 3 years olds and 18 year olds, or teaching English, music or PE, the reality is that these can be rather different. Taking that further, we might even have two year 3 classes; same age and same subject, but with an entirely different profile of prior knowledge, motivation, or attitude to learning that might benefit from entirely different approaches.

Seeking consistency fails to take into account the complexity of schools, a tiny fraction of which is described above. I’d argue that it is not consistency that is desirable but coherence.

Chasing consistency of teaching approach might lead to superficial implementation of ideas; mimicry to please or to avoid unwanted attention from clipboard wielding leaders. Striving for coherence of teaching approach might lead to adaptive expertise, emergence of increasingly effective strategies and genuinely meeting the needs of children.

We’ve probably all been through a process of standardising teaching in some form or another; some upfront training, leaders showing us techniques and us implementing that in our classrooms; then some sort of monitoring where we demonstrate that we can do the desired strategy.

What I’m proposing is things that we might have to do as leaders to achieve coherent teaching approaches across the school:

- Work on shared beliefs

- Work on shared language

- Work on a shared mental model

- Invite challenge

- Look outwards

- Define the what, why and when of strategies

Work on shared beliefs

Shared beliefs are the most substantial part of the culture iceberg. Viviane Robinson says that we spend too much time seeking to influence teachers’ actions and not enough time seeking to influence the underlying beliefs that sustain them:

So how do we work on shared beliefs? There are a couple of options but first they need bringing to the surface. We need to know what drive others’ behaviours rather than make assumptions. Robinson’s open to learning conversations gives a structure for doing this:

Leaders will probably have a strong opinion on the kinds of beliefs that should be shared amongst the team but this should have more substance than the typical work on values that a lot of organisations engage in which can be a bit vague and horoscopey. The kind of detail of underlying beliefs that actually sustain behaviours in the classroom by teachers is far more than than the usual values that schools adopt such as integrity or resilience or success and the like. Some examples below:

And now back to how. Most importantly, they need to be talked about! Leaders have influence and if we’re paying attention to certain beliefs though what we’re saying and how we’re behaving, we are demonstrating their importance. And remember it is beliefs relating to sustaining the actions that teachers take that are important, not vague values.

Work on shared language

We might be talking about the same thing but if we have different names for them, lots can be lost in translation. AFL, assessment for learning, responsive teaching and adaptive teaching have lots in common but but different names. Different names can cause confusion and confusion can affect teachers’ behaviours. So let’s name teaching strategies and the ideas that sit beneath them

Work on a shared mental model

A shared mental model pulls together beliefs about what great teaching is with the language used to describe the many parts to it. Here are some examples:

In this model, the principles at the top serve as some underlying beliefs that I believe to be of value. The problems to solve row does a similar job in telling the story of my belief that teaching is problem solving. And the example strategies / techniques reinforces this. Teachers could choose from these strategies in order to the solve the problem that they are experiencing. By naming them, we’re setting our stall out about what we call important behaviours.

Here’s another one:

Here, I’ve sought a different degree of organisation to the table in the former, using a concept map. The reason for organisation is an important one. Ausubel’s work on meaningful learning, popularised by Sarah Cottinghat is certainly applicable to the meaningful learning of teachers, not just children. We want teachers to have a vast, accessible, stable, connected and organised body of knowledge about teaching to support continuous learning.

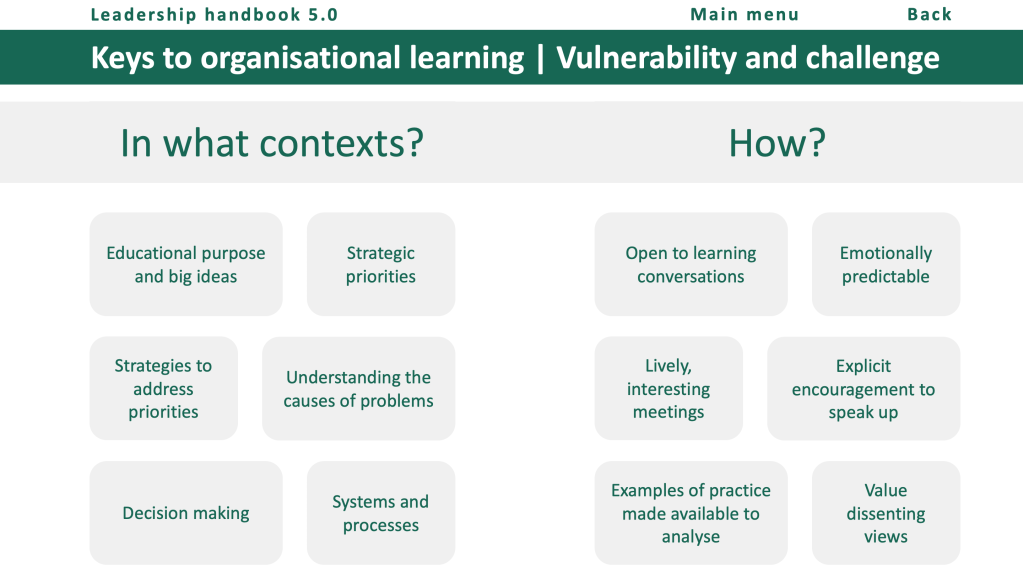

Invite challenge

School is far too complex for any one individual to have the monopoly over what makes great teaching. So we need challenge. One size does not fit all and coherence is preferable to consistency, even between seemingly similar groups.

Is this right for our oldest and youngest children? What about children with SEND? Is it right in every subject? Does different lesson content require different approaches? All of these challenges and more need to be encouraged and tested.

Look outwards

Our schools can easily be echo chambers and even if we have plenty of challenge within our team, there is always someone, somewhere who can offer additional challenge where we can learn from different contexts.

Even if we’re experiencing great success, we ought to look outwards to what others are doing and thinking about. Indeed while most of our time as leaders is addressing in school variance, a little of our time should be spent on (and, playing to colleagues’ strengths, some of the team) should pay attention to innovation.

Define the what, why and when of strategies

At the heart of a coherent approach to teaching rather than a consistent one is agency. I say agency rather than autonomy or alignment thanks to Matt Evans’ blog:

Alignment without agency is automatons following instructions. What a healthy aligned system requires is that the agents within it help the system to dynamically evolve. Rather than losing control through system alignment, agents must feel that they are able to handle the situations they face better and also contribute to the system-knowledge that helps others to do the same.

Evans 2024

A lot of pedagogical frameworks describe the what very well – to most, this is the most important element to communicate. Many have a solid why through reference to some form of evidence. Not many delve into the when. Consider this caricature of implementing a teaching strategy:

School leaders decide to work with teachers on talk partners. It is obviously important so teachers spend time setting up routines for talk partners and build it into their practice. A leader goes to observe a teacher and of course the teacher is keen to show the leader how they have implemented talk partners. It is a maths lesson and the teacher sets up this talk partner moment:

How many degrees is a right angle? Talk to the person next to you…

Now clearly, talk partners to answer a factual recall question isn’t going to the most appropriate form of response to that question. Because choice over when to use a strategy has to be exercised.

Summary

Aim for a coherent approach to teaching, not a consistent one.

To achieve coherence:

- Work on shared beliefs

- Work on shared language

- Work on a shared mental model

- Invite challenge

- Look outwards

- Define the what, why and when of strategies

This is an incredible post. Its really made me reflect.

Thanks

LikeLiked by 1 person